AeroGenie — Your Intelligent Copilot.

The Hidden Economics of Fleet Commonality (And How to Reduce Overhead Costs)

June 24, 2025

Why do airlines like Ryanair and Southwest bet big on one aircraft type? The answer lies in lower costs, faster maintenance, and smarter operations—but the real story is more complex.

What is fleet commonality, and why does it matter?

In a boom-and-bust industry like aviation, the smallest of logistical snags can upend an airline’s financials. Fuel prices, labor costs, and the vagaries of global trade throw out plenty of challenges for modern fleets.

Big data, AI technology, and revised trade policies are touted as the cure-all, but there are other quieter strategies in the mix: fleet commonality. Simply put, fleet commonality refers to an airline operating one standardized set of aircraft. Typically, the planes are all from the same manufacturer, often the same model family, to cut complexity and boost efficiency.

Fleet commonality can simplify operations and deliver economics at scale. Fewer aircraft types mean fewer pilot certifications needed, streamlined maintenance, and less capital tied up in excess inventory reserves. Airfares drop for customers, and carriers benefit from lower overhead, faster turnaround times, and greater operational resilience.

Southwest Airlines is a well-known example. For decades, the carrier has flown Boeing 737 variants. This singular focus allows any of its pilots to fly any aircraft in its fleet, which enables hyper-flexible crew scheduling and eliminates delays caused by aircraft type mismatches (Risk Management Study Group).

More broadly, airlines also benefit from unified systems across cockpits, cabins, and even software interfaces, further minimizing the need for specialized training or equipment.

This principle of sameness extends to manufacturers too: Airbus has long marketed its A320 family’s cross-crew qualification (CCQ) system as a core cost-saving feature (Airbus Newsroom).

Whether you're operating a dozen regional jets or a few hundred narrowbodies, commonality can drastically reduce what it costs to keep your planes in the air.

The hard numbers: Where the savings come from

When it comes to the cost savings of fleet commonality, here’s how the math works.

1. Training costs plummet

Training crew across multiple aircraft types is expensive. With fleet commonality, airlines avoid needing duplicative pilot and technician certifications. Ryanair, which operates only Boeing 737 planes, has explicitly credited this strategy for lowering training expenses and preventing talent poaching from Airbus-heavy carriers. Since Airbus and Boeing require different certifications, Ryanair pilots aren’t easily lured away by competitors flying the A320 family (Simple Flying).

2. Maintenance gets leaner

Maintenance is simplified for airlines with uniform fleets. Engineers become deeply familiar with one system, allowing for faster repair turnaround times and fewer human mistakes. In a 2010 study, Brüggen & Klose found a direct correlation between fleet commonality and improved operating performance among low-cost carriers (ScienceDirect.com: Journal of Air Transport Management).

3. Parts inventory shrinks

The fewer aircraft types you operate, the fewer spare parts you need. This brings cascading benefits for storage and procurement. It also significantly cuts time-to-service when parts need replacing. Southwest Airlines, for instance, stockpiles critical 737 components to minimize supplier delays in this form of risk management that wouldn’t be nearly as successful with a varied fleet.

4. Scheduling becomes plug-and-play

When every aircraft is the same, you can assign any crew to any plane and operate any route with less friction. That flexibility matters especially during peak seasons, flight redirects, or other disruptions, allowing airlines to adapt without fleet-specific bottlenecks.

The Southwest & Ryanair playbook: Single-type fleets in action

As highlighted earlier, Southwest Airlines has become synonymous with fleet commonality. Since its founding in 1967, Southwest has operated a single aircraft type: the Boeing 737 as both a branding and economic play (Southwest 50 Years).

This single-model fleet simplifies pilot training, slashes maintenance complexity, and streamlines crew scheduling. Any pilot can fly any plane, any mechanic can service any aircraft, and the airline can react dynamically to delays or route changes (Risk Management Study Group).

The math behind the theory plays out. As of March 2025, Southwest operated more than 800 Boeing 737 aircraft, making it the world’s largest operator of the type (Southwest Newsroom). It also held one of the highest aircraft utilization rates in the industry: over 9.5 hours per aircraft per day, according to investor reports.

Ryanair, meanwhile, has taken a similar approach with its trans-Atlantic flights. With a commitment to Boeing 737s, starting from the 737-200 up to the MAX 8-200, the Irish low-cost carrier avoids duplicating infrastructure, pilot certifications, and MRO processes. Ryanair also leverages this commonality to extract bulk discounts from Boeing, with credit memoranda and concessions reducing acquisition and lifecycle costs.

In its FY2024 report, Ryanair explicitly states that operating a single aircraft type is vital to limiting costs. Airline CEO Michael O’Leary states, “The Ryanair formula of low fares, quick and efficient turnarounds, a fleet of [exclusively] new and fuel-efficient Boeing 737 aircraft continues to succeed across Europe despite external challenges and intense competition in all markets” (Ryanair Group Annual Report 2024).

For low-cost airlines in particular, operating single-type fleets can prove smart and profitable.

The flip side: When fleet commonality can hurt you

Fleet commonality, for all its advantages, carries risks too, notably concentration risk. When your operation relies on a single manufacturer, model, or engine type, any disruption in that manufacturer’s supply chain can have a devastating domino effect across your entire business.

Wizz Air

Case in point: the Pratt & Whitney PW1100G engine crisis. Operators of the Airbus A320neo and A220 families—powered by the PW1100G engine—have been forced to ground fleets due to inspection and durability issues.

Wizz Air, a low-cost Hungarian carrier, was forced to ground over 40 aircraft in 2024 (Civil Aviation Authority). As one of Europe’s most aggressive Airbus users, these engine woes have sidelined flight operations indefinitely.

In early 2025, Wizaz’s CEO Jozsef Varad said that planes will remain grounded for several years. “I think they are trying their best, but this is going to be a long process. At the beginning, we felt maybe 18 months, maybe two years. This is clear [now] it’s more like a four-to five-year issue” (Reuters).

Frontier Airlines

Frontier Airlines, with over 100 Airbus A320neo family aircraft, warned in its SEC filings that its dependence on a single airframe and engine combination could "materially impact operations" if delivery delays or technical issues arise.

Their filings even state: “A critical cost-saving element of our business strategy is to operate a single-family aircraft fleet; however, our dependence...makes us vulnerable to any delivery delays, design defects, mechanical problems or other technical or regulatory issues.” (Frontier Q3 2023 SEC filing)

Lion Air

In a final sobering example, the infamous 737 MAX grounding of 2019–2020. Carriers that were heavily reliant on the MAX, like Lion Air, faced serious revenue shortfalls, forced to scramble for capacity or delay expansion (Harvard Law School, World Bank).

In Lion Air’s case, its heavy bet on the MAX in a bid to streamline maintenance, reduce fuel costs, and support its rapid growth across Southeast Asia, backfired catastrophically.

When the fleet was grounded following two fatal crashes involving that very model (one of them Lion Air Flight 610), the airline was left with limited operational flexibility. Its commitment to a single aircraft type meant there was no immediate backup fleet to plug the gap. Chartering or leasing alternatives at short notice drove up costs, while grounded aircraft continued to rack up depreciation and parking fees without generating revenue.

A once strategic cost-saving decision, fleet commonality, became a bottleneck that froze capacity, strained financials, and eroded customer confidence.

Betting everything on one aircraft family works great—until it doesn’t. The trick is knowing when that risk tips the scales so you can spread out your eggs across several baskets.

The case for sub-fleets or mixed OEMs

While fleet commonality offers undeniable savings, many airlines, especially legacy carriers and global network operators, deliberately choose to run mixed fleets. This mixed approach gives aviation companies the flexibility to optimize for range, passenger capacity, and supplier risk — wins that can outweigh the benefits of standardization.

American Airlines, Turkish Airlines, Delta Air Lines, and China Southern, for example, all operate both Airbus A320neo and Boeing 737 MAX aircraft. At first glance, this would seem to increase complexity: pilots must be cross-trained, mechanics need separate certifications, and spare parts inventories double. But there’s a reason they do it.

The core reason, however, is risk diversification. As seen with the 737 MAX and PW1100G engine crises, relying too heavily on one airframe or one powerplant introduces systemic risk. A dual-OEM strategy allows airlines to pivot if one aircraft type is grounded or delayed.

Then there’s the technical flexibility. While the A320neo and 737 MAX families are similar, they are not interchangeable. The A321XLR, for example, can fly up to 4,700 nautical miles, significantly outpacing the range of the 737 MAX 10. For airlines expanding into long-haul markets, like transatlantic or secondary city pairings, that extra range can be a game-changer.

Fleet delivery timelines are another consideration. Well before 2025 tariff uncertainty, backlogs at Boeing and Airbus were years-long. Having both OEMs in your procurement playbook, however, increases access to near-term delivery slots. Airlines like easyJet and United have strategically shifted manufacturers not just for price but for availability.

In short, agility comes with a price tag. A hybrid fleet approach is more expensive up front, but it pays off when the market shifts or a manufacturer falters.

Military parallels: What the USAF teaches us about commonality

The logic behind fleet commonality isn’t unique to commercial aviation. The United States Air Force (USAF) has long wrestled with the same tradeoff: efficiency vs. flexibility.

In 2024, the USAF publicly confirmed a strategic shift toward parts commonality across a “collaborative aircraft fleet” (Air Force). Through this approach, building aircraft with shared systems and components even if they serve different missions, the Air Force aims to reduce its footprint and lower the cost of spare parts needed during forward deployments (TWZ).

The USAF approach shows the other side of fleet commonality. It’s not always about lowering costs; in some scenarios, uniformity can increase speed and resilience. A common component ecosystem allows technicians to adapt and repair systems in remote work environments without having to fly in custom parts or wait for a specifically trained field expert. It mirrors what Southwest does at a commercial scale: every plane is “fixable” by every mechanic at every location serviced.

In both commercial and military settings, the takeaway is clear: the more uniform your tools and platforms, the faster you can respond to disruptions—and with fewer resources needed.

But even the USAF doesn’t go all-in. Their approach is modular: a mix of shared architecture with mission-specific customizations. Airlines considering mixed fleets may find this hybrid strategy of using common parts in a diversified aircraft fleet useful to emulate.

Strategic mitigation: How to reduce risk without losing the benefits

Some of the smartest players in the industry are pursuing hybrid fleet strategies in order to maximize the benefits of aircraft uniformity while proactively managing risk.

Here’s how they’re doing it:

Stockpile critical components

Southwest Airlines maintains a strategic reserve of Boeing 737 parts, helping ensure that a sudden disruption in the supply chain doesn’t cripple operations (RMS Study Group). Airlines that operate a uniform fleet can make this approach even more effective by concentrating their capital into a leaner, more targeted parts inventory.

Diversify within the supply chain

Even when an airline sticks to one airframe family, it can diversify across maintenance providers, engine variants, or avionics suppliers. Frontier, for example, equips its A320neo family aircraft with both Pratt & Whitney and CFM International engines, creating redundancy even within a “single” fleet.

Leverage sub-fleets

Some carriers adopt “sub-fleet segmentation.” Here, fleets use aircraft from the same family but with varying capacities or configurations. Ryanair’s use of both the 737-800 and the denser 737 MAX 8-200 lets it match capacity to route demand without losing operational commonality.

Model-based scenario planning

The best risk and cost mitigation strategies might be invisible to passengers. Airlines use forecasting models and scenario simulations to map the impact of supply disruptions, mechanical recalls, or OEM delivery delays. This data feeds into aircraft acquisition strategies, informing when to buy, retire, or diversify.

Consider crew pooling and scheduling tech

Flexible crew scheduling software (and cross-certification within aircraft families) can offer some of the same benefits of commonality even in semi-diverse fleets. For example, Airbus’s cross-crew qualification system allows pilots to move between the A320 and A330 families with minimal retraining (Airbus Newsroom).

The key isn’t to eliminate fleet diversity at all costs, but rather to build a resilient operating model that’s prepared when things go sideways.

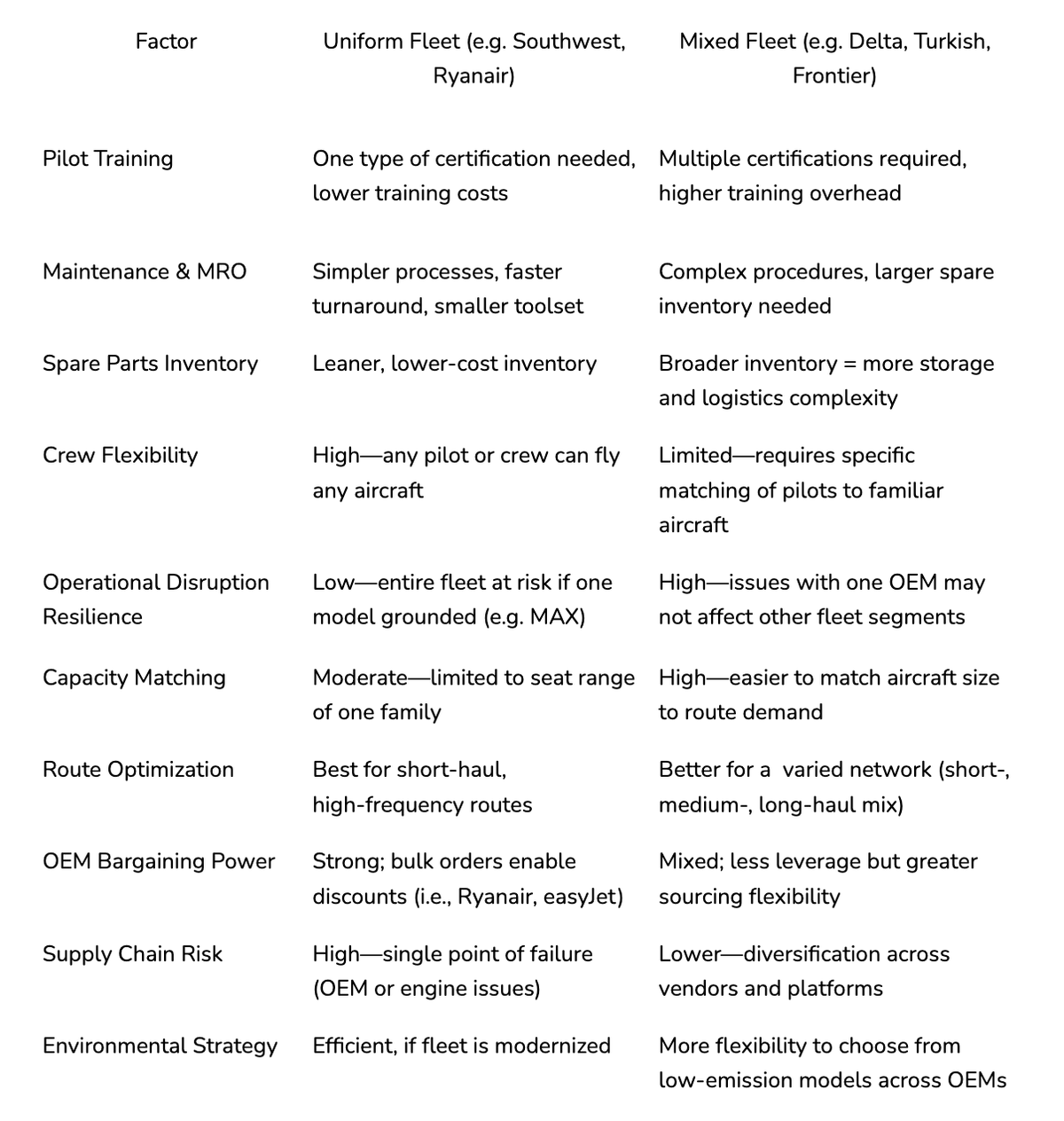

📊 Uniform vs. mixed fleets: A strategic comparison

FAQs

What’s the most common aircraft used for single-type fleets?

Among low-cost carriers, the Boeing 737 is king. Southwest Airlines operates more than 800 Boeing 737s, making it the largest 737 operator in the world. Ryanair also sticks exclusively to the 737, citing efficiency, cost savings, and better bargaining power with Boeing.

Airbus isn’t far behind. EasyJet runs a streamlined fleet of A320 family aircraft, including A319s, A320s, and A321neos, taking full advantage of cross-crew qualifications and shared MRO infrastructure. Meanwhile, some air freight companies adopt fleet uniformity to streamline their operations.

SmartLynx Airlines focuses exclusively on Airbus A320 and A321 aircraft, simplifying maintenance and training processes. Qatar Airways Cargo has transitioned to an all-Boeing 777 Freighter fleet, enhancing efficiency and sustainability.

Different models dominate in different regions and industries, but the formula stays the same: pick one, scale it, and simplify everything else.

How many aircraft types do diverse-fleet airlines use?

For large passenger airlines, the variety can be significant. Delta Air Lines, for example, operates a diverse mainline fleet comprising 985 aircraft across 17 distinct passenger aircraft types (Delta).

Delta’s mix includes a balanced mix of Airbus and Boeing models, such as the Airbus A220, A319, A320, A321, A330, A350, and Boeing 717, 737, 757, and 767 variants. Delta's strategy of maintaining a mixed fleet allows for operational flexibility and route optimization across its extensive network.

Why are some airlines adding back-up OEMs even after standardizing?

Airlines are learning the hard way that even a perfectly uniform fleet does not guarantee simpler or cheaper operations. That’s why some carriers are building controlled diversity into their strategies, such as locking in secondary engine suppliers, using alternate MRO partners, or introducing a second airframe family in low-volume sub-fleets.

What’s the tipping point for switching to a mixed fleet?

The math shifts when route demands outgrow your fleet’s capabilities or when OEM delivery backlogs start threatening expansion.

Long-range narrowbodies, high-density short-haulers, and faster delivery slots can often justify a second aircraft type, despite the added cost. The trick is to use strategic forecasting tools to know your break-even point and model the operational ROI before you commit.

Key takeaways for fleet strategy in 2025 and beyond

As global demand rebounds and supply chains remain strained, airlines face a strategic crossroads: double down on fleet commonality, diversify to mitigate risk, or do both?

Here’s what 2025 tells us:

- Fleet commonality still reigns supreme for cost-cutting and operational simplicity, especially for short-haul, high-frequency carriers like Ryanair, Southwest, or GOL.

- The risks are real: Overreliance on one OEM or engine type can create bottlenecks, revenue shortfalls, and reputational harm.

- Mixed or modular strategies are gaining ground: Sub-fleets, split engine contracts, and dual OEM orders are on the rise as a hedge against disruption.

- Military logic supports the trend: The USAF’s modular commonality model shows that redundancy means greater agility and responsiveness..

Whether you’re an airline planning your next order or a supply chain executive weighing the cost of standardization, one truth is clear: fleet strategy is core to your business continuity plan.

In a world of constrained deliveries, climate extremes, and geopolitical threats, preparedness and adaptability matter more than ever. Here, fleet commonality can become a major infrastructure advantage, paired with intelligent procurement, resilient supply chains, and tech-powered foresight. As we've seen in some notable airline examples, the economics of commonality can save millions, but only if you can see potential vulnerabilities before they ground your fleet.

ePlaneAI is that extra set of eyes. Our AI-powered procurement platform helps aviation leaders streamline parts sourcing, monitor supplier risk, and maintain consistent operations, whether you're running a single-model fleet or a diverse one.

With blockchain traceability, predictive analytics, and real-time visibility, ePlaneAI turns procurement into your upper hand in the market.

👉 Explore how ePlaneAI helps modern fleets stay flying.

Aviation Maintenance Trends That May Gain Momentum in Uncertain Circumstances

Aircraft are staying in service longer, supply chains are a powder keg, and the tech is evolving overnight. Discover the maintenance trends gaining momentum and what they mean for operators trying to stay airborne and profitable.

February 2, 2026

ePlane AI at Aircraft IT Americas 2026: Why Aviation‑Native AI Is Becoming the New Operational Advantage

The aviation industry is entering a new phase where operational performance depends not just on digital tools, but on intelligence.

October 2, 2025

Choosing the Right Aircraft Parts with Damage Tolerance Analysis

The future of aviation safety is all about the parts. Authentic, traceable parts bring optimal damage tolerance and performance to fleets for maximum safety and procurement efficiency.

September 30, 2025

How to Enter New Aviation Markets: The Complete Guide for Parts Suppliers

Breaking into new aviation markets? Learn how suppliers can analyze demand, manage PMA parts, and build airline trust. A complete guide for global growth.